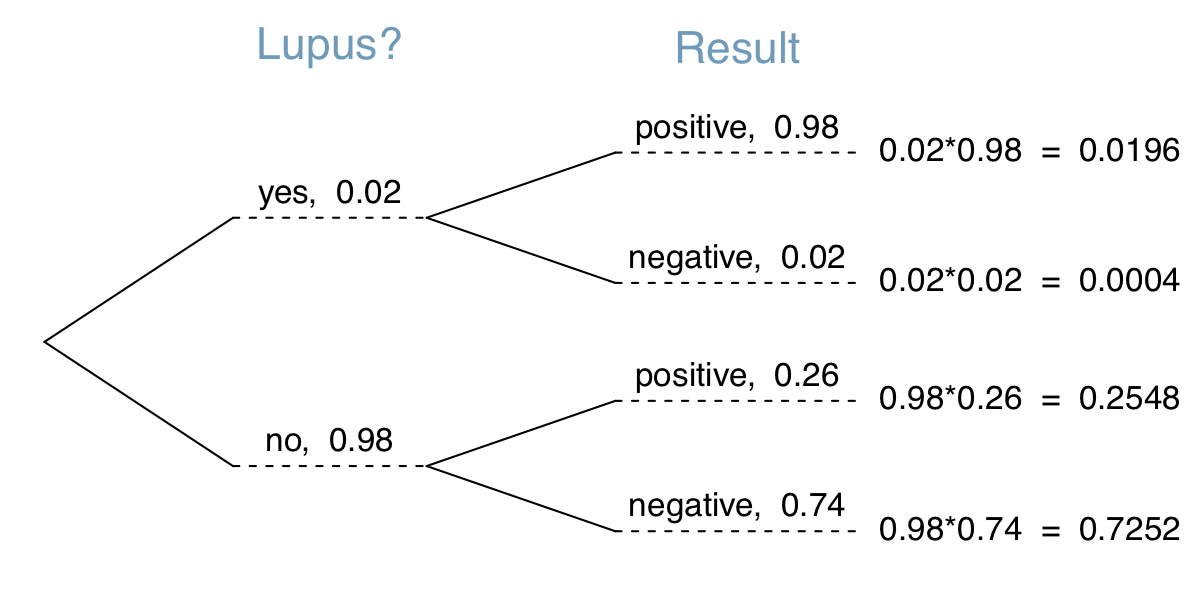

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Part 2: Probability ### Sam Tyner ### 2018/06/14 --- class: primary # Textbook These slides are based on the book *OpenIntro Statistics* by David Diez, Christopher Barr, and Mine Çetinkaya-Rundel The book can be downloaded from [https://www.openintro.org/stat/textbook.php](https://www.openintro.org/stat/textbook.php) Part 2 Corresponds to Chapter 2 of the text. Sections 2.1-2.4 correspond to sections 2.1, 2.2, 2.4, 2.5 of the text. --- class: primary # Outline - Defining Probability (2.1) - Conditional probability (2.2) - Random variables (2.3) - Continuous distributions (2.4) --- class: inverse # Section 2.1: Defining Probability --- class: primary # What is probability?  --- class: primary # Very formal definition > The probability of an outcome is the proportion of times the outcome would occur if we observed the random process an infinite number of times. - What is an outcome? - What is a random process? --- class: primary # Very formal definition > The probability of an outcome is the proportion of times the outcome would occur if we observed the random process an infinite number of times. - What is an outcome? .red[Any event or outcome of interest] - What is a random process? .red[Anything that causes events at random that can theoretically happen an infinite number of times] --- class: primary # Examples Random Process | Outcome :-------------:|:-------: Roll of a die | 6 Flip of a coin | Heads Others? --- class: primary # Some notation `\(P(A)\)` - often used to denote the probability of event `\(A\)` Probability is always between 0 and 1. In symbols: `\(0 \leq P(A) \leq 1\)` Probability can also be expressed as a percentage: `\(100 \times P(A) \%\)` - e.g. `\(P(A) = 0.45\)` is equivalent to `\(45\%\)`, `\(P(A) = 0.015\)` is equivalent to `\(1.5\%\)` Example: - Suppose we are rolling a fair 6-sided die. There are 6 outcomes, `\(\{1,2,3,4,5,6\}\)`, and we are interested in the outcome `\(1\)`. - What is `\(P(1)\)`? --- class: primary # Law of Large Numbers (Activity) - Suppose we are rolling a fair 6-sided die. There are 6 outcomes, `\(\{1,2,3,4,5,6\}\)`, and we are interested in the outcome `\(1\)`. -- - We roll the die `\(n\)` times. The symbol `\(\hat{p}_n\)` represents the proportion of observed outcomes that are `\(1\)` after the first `\(n\)` rolls. -- - As the number of rolls ( `\(n\)` ) increases, `\(\hat{p}_n\)` (observed probability) will get closer and closer to the theoretical probability `\(p\)`. -- - For this example, `\(p = \frac{1}{6}\)` -- - This is due to the **Law of Large Numbers**: the tendency of observed probabilities to approach theoretical probabilities as the number of total observations increases. --- class: primary # Disjoint outcomes - Two outcomes are **disjoint** (also called **mutually exclusive**) if they cannot both happen - Example: In a single roll of a die, the outcome `\(1\)` and the outcome `\(2\)` are disjoint, because they cannot both happen. - Example: In a single roll of a die, the outcome `\(1\)` and the outcome "rolling an odd number" are NOT disjoint because if you roll a `\(1\)`, both outcomes have happened. --- class: primary # Probability of disjoint outcomes - Let `\(A\)` and `\(B\)` denote 2 disjoint events. Their probabilities are denoted `\(P(A)\)` and `\(P(B)\)` - We are interested in the probability of either `\(A\)` or `\(B\)` occurring: denoted `\(P(A \text{ or } B)\)`. - To compute this probability, we use the **addition rule of disjoint outcomes** `$$P(A \text{ or } B) = P(A) + P(B)$$` - In words: if two outcomes are disjoint, the probability that one of the two will occur is the sum of their individual probabilities - Addition rule applies for more than 2 outcomes as well as long as ALL outcomes are **disjoint**. --- class: primary # Probabilities: not disjoint How do you compute probabilities when events are NOT disjoint? <!--latex below taken directly from os3 github page--> Example: Standard deck of cards  What are some non-disjoint events? --- class: primary # Non-disjoint examples When drawing a card at random from a deck of cards: - Let `\(A\)` represent the outcome that the card is a diamond - Let `\(B\)` represent the outcome that the card is a face card - What is the probability of `\(A\)` or `\(B\)`? Question: why aren't these events disjoint? --- class: primary # Non-disjoint examples When drawing a card at random from a deck of cards: - Let `\(A\)` represent the outcome that the card is a diamond - Let `\(B\)` represent the outcome that the card is a face card - What is the probability of `\(A\)` or `\(B\)`? Question: why aren't these events disjoint? Because .red[J]♦️, .red[Q ]♦️, .red[K]♦️ are outcomes that fall into `\(A\)` and `\(B\)`. --- class: primary # Probability example For non-disjoint events: If we used the addition rule, the outcomes .red[J]♦️, .red[Q]♦️, .red[K ]♦️ would be counted twice: once for outcome `\(A\)`, and once for outcome `\(B\)`. `\begin{align*} P(A \text{ or } B) & = P( ♦️ \text{ or face card}) \\ & = P(♦️) + P(\text{face card}) - P(♦️ \text{ AND face card}) \\ & = \frac{13}{52} + \frac{12}{52} - \frac{3}{52} \\ & = \frac{22}{52} = \frac{11}{26} \approx 0.4231 \equiv 42.31\% \end{align*}` --- class: primary # General Addition Rule If `\(A\)` and `\(B\)` are any two events, disjoint or not, then the probability that at least one of them will occur is `$$P(A \text{ or } B) = P(A) + P(B) - P(A \text{ and } B)$$` where `\(P(A \text{ and } B)\)` is the probability that both events occur. Note: If `\(A\)` and `\(B\)` are disjoint, what does `\(P(A \text{ and } B)\)` equal? --- class: primary # Probability distributions A (discrete) **probability distribution** is a table of all disjoint outcomes and their associated probabilities. Example: consider the sum of a roll of two 6-sided dice. `\(\frac{\text{Roll } 1 \rightarrow}{\text{Roll } 2 \quad \downarrow}\)`|1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 -|--|---|---|---|---|--- 1|2 |3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 2|3 |4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 3|4 |5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 4|5 |6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 5|6 |7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 6|7 |8 | 9 | 10 | 11| 12 --- class: primary # Probability distributions Sum | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 :-----------|:-:|:-:|:-:|:-:|:-:|:-:|:-:|:-:|:--:|:--:|:--: Probability | `\(\frac{1}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{2}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{3}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{4}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{5}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{6}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{5}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{4}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{3}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{2}{36}\)` | `\(\frac{1}{36}\)` --- class: primary # Probability Distributions A probability distribution is a list of the possible outcomes of a random process with corresponding probabilities that satisfies three rules: 1. The outcomes listed must be disjoint. 2. Each probability must be between 0 and 1. 3. The probabilities must total 1. --- class: primary # Probability Distributions <img src="probability_files/figure-html/probdist-1.png" width=".49\linewidth" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /><img src="probability_files/figure-html/probdist-2.png" width=".49\linewidth" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: primary # Complement of an Event - The **sample space** ( `\(\mathcal{S}\)` ) is a list of all possible outcomes of a random process - For an event `\(A\)`, the **complement** of `\(A\)` , denoted `\(A^c\)` is the set of all outcomes in the sample space that are not in `\(A\)` - For example, for a 6-sided die, `\(\mathcal{S} = \{1,2,3,4,5,6\}\)` - Let `\(A = \{2,3\}\)` be the event that the outcome of a die roll is `\(2\)` or `\(3\)`. - The complement of `\(A\)` is `\(A^c = \{1,4,5,6\}\)` --- class: primary # Complement of an Event - `\(A\)` and `\(A^c\)` are **disjoint** by definition - `\(P(A \text{ or } A^c) = 1\)` - `\(P(A \text{ or } A^c) = P(A) + P(A^c)= 1\)` - `\(P(A^c) = 1 - P(A)\)` --- class: primary # Independence - Two random processes are **independent** if knowing the outcome of one doesn't inform the outcome of the other. - Example: the processes "rolling a die" and "flipping a coin" are independent - Example: rolling 2 dice - Suppose one die is red and the other is white. We roll the red die, then the white die. What is the probability that they will both be `\(1\)`? --- class: primary # Independence - Two random processes are **independent** if knowing the outcome of one doesn't inform the outcome of the other. - Example: the processes "rolling a die" and "flipping a coin" are independent - Example: rolling 2 dice - Suppose one die is red and the other is white. We roll the red die, then the white die. What is the probability that they will both be `\(1\)`? - .red[Solution]: `\(P( white = 1 , red =1)= \frac{1}{6} \times \frac{1}{6} = \frac{1}{36}\)` --- class: primary # Multiplication Rule **This rule applies only to independent processes!** If `\(A\)` and `\(B\)` represent events from two different and independent processes, then the probability that both `\(A\)` and `\(B\)` occur can be calculated as the product of their separate probabilities: `$$P(A \text{ and } B) = P(A) \times P(B)$$` - This is also true for more than 2 independent events, as long as they are ALL independent. - This is also used as a definition to determine if two events are independent. i.e. if we know `\(P(A)\)`, `\(P(B)\)`, and `\(P(A \text{ and } B)\)` , we can figure out if the events are independent. --- class: primary # Your Turn 2.1.1 Determine if the statements below are true or false, and explain your reasoning. 1. If a fair coin is tossed many times and the last eight tosses are all heads, then the chance that the next toss will be heads is somewhat less than 50%. 2. Drawing a face card (jack, queen, or king) and drawing a red card from a full deck of playing cards are mutually exclusive events. 3. Drawing a face card and drawing an ace from a full deck of playing cards are mutually exclusive events. --- class: primary # YT 2.1.1 (soln.) Determine if the statements below are true or false, and explain your reasoning. 1. If a fair coin is tossed many times and the last eight tosses are all heads, then the chance that the next toss will be heads is somewhat less than 50%. .red[False. The probability of heads on a flip of a fair coin is always 0.5. Thinking otherwise is called the *Gambler's Fallacy*] 2. Drawing a face card (jack, queen, or king) and drawing a red card from a full deck of playing cards are mutually exclusive events..red[False. The red suits (heart, diamond) have face cards.] 3. Drawing a face card and drawing an ace from a full deck of playing cards are mutually exclusive events. .red[True. A card cannot be a face card and an ace.] --- class: primary # Your Turn 2.1.2 Below are four versions of the same game. Your archnemesis gets to pick the version of the game, and then you get to choose how many times to flip a coin: 10 times or 100 times. Identify how many coin flips you should choose for each version of the game. It costs $1 to play each game. Explain your reasoning. 1. If the proportion of heads is larger than 0.60, you win $1. 2. If the proportion of heads is larger than 0.40, you win $1. 3. If the proportion of heads is between 0.40 and 0.60, you win $1. 4. If the proportion of heads is smaller than 0.30, you win $1. --- class: primary # YT 2.1.2 (soln.) Below are four versions of the same game. Your archnemesis gets to pick the version of the game, and then you get to choose how many times to flip a coin: 10 times or 100 times. Identify how many coin flips you should choose for each version of the game. It costs $1 to play each game. Explain your reasoning. 1. If the proportion of heads is larger than 0.60, you win $1. .red[10 tosses. Higher variability with fewer tosses] 2. If the proportion of heads is larger than 0.40, you win $1. .red[100 tosses. More tosses will be closer to the mean (0.5), which is above 0.4.] 3. If the proportion of heads is between 0.40 and 0.60, you win $1. .red[100 tosses. Same reason as 2.] 4. If the proportion of heads is smaller than 0.30, you win $1. .red[10 tosses. Same reason as 1.] --- class: primary # Your Turn 2.1.3 Each row in the table below is a proposed grade distribution for a class. Identify each as a valid or invalid probability distribution, and explain your reasoning. No. | A | B | C | D | F ----|---|---|---|---|--- 1 |0.3|0.3|0.3|0.2|0.1 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 3 |0.3|0.3|0.3| 0 | 0 4 |0.3|0.5|0.2|0.1|-0.1 5 |0.2|0.4|0.2|0.1|0.1 6 | 0 |-0.1|1.1|0 |0 --- class: primary # YT 2.1.3 (soln.) Each row in the table below is a proposed grade distribution for a class. Identify each as a valid or invalid probability distribution, and explain your reasoning. No. | A | B | C | D | F ----|---|---|---|---|--- 1 |0.3|0.3|0.3|0.2|0.1 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 3 |0.3|0.3|0.3| 0 | 0 4 |0.3|0.5|0.2|0.1|-0.1 5 |0.2|0.4|0.2|0.1|0.1 6 | 0 |-0.1|1.1|0 |0 .red[Only 2 and 5 are valid distributions. 1 and 3 are not valid because the probabilities do not sum to 1. 4 and 6 are not valid because they have "probabilities" less than 0 or greater than 1.] --- class: inverse # Section 2.2: Conditional probability --- class: primary # Example Recall the Your Turn 1.7.2 from Part 1. Is the probability of supporting the DREAM act the same for conservatives as it is for liberals? Why? <img src="probability_files/figure-html/dream-1.png" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: primary # Idea **Conditional probablility** refers to a probability of an event when we already know that another event has occurred. - Example: Suppose we know the ideology (conservative, liberal, or moderate) of a randomly selected voter in the US. Does knowing that information change your guess about their support for the DREAM act? We'll get to a more formal definition of conditional probability after some preliminaries. --- class: primary # Marginal Probability Here is the raw data for the DREAM act plot: <table> <caption>Support by ideology for the DREAM act</caption> <thead> <tr> <th style="text-align:left;"> Support </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> Conservative </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> Liberal </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> Moderate </th> <th style="text-align:right;"> Total </th> </tr> </thead> <tbody> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> No </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 151 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 52 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 161 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 364 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Not sure </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 35 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 9 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 28 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 72 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Yes </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 186 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 114 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 174 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 474 </td> </tr> <tr> <td style="text-align:left;"> Total </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 372 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 175 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 363 </td> <td style="text-align:right;"> 910 </td> </tr> </tbody> </table> The **marginal probabilies** are the probabilities based on a single variable without regard to any other variables. (Here, row and column totals.) For example: `\(P(\text{support }= \text{ yes}) = \frac{474}{910} \approx 0.52\)` --- class: primary # Joint probability A probability of outcomes for two or more variables or processes is called a **joint probability**. Example: `\(P(\text{support }= \text{ yes} , \text{ideology }= \text{ conservative}) = \frac{186}{910} = 0.20\)` Notation: Inside `\(P()\)`, `\(P(A,B)\)` means `\(P(A \text{ and } B)\)` --- class: primary # Conditional probability - We know there is a relationship between ideology and support of the DREAM act. - Conditional probability is the idea that we can use knowledge of the relationship to improve probability estimation - Example: `\(P(\text{support = yes}) = 0.52\)` but what if we know the person is ideologically liberal? Does that change the probability? `$$P(\text{support = yes } \textit{given } \text{ ideology = liberal} ) = \frac{114}{175} = 0.65$$` - This is a **conditional probability** because we computed probability of one outcome under a condition (ideology = liberal) - `\(P(\text{support = yes } \textit{given } \text{ ideology = liberal} )\)` is the same as `\(P(\text{support = yes } |\text{ ideology = liberal} )\)` --- class: primary # Conditional probability - To obtain the conditional probability of "support = yes" given "ideology = liberal", we first consider only the respondents who say they are liberal (175 respondents), then look at the fraction of those who support the DREAM act: `\begin{align*} & P(\text{support = yes } |\text{ ideology = liberal}) \\ & = \frac{\# \text{support = yes and ideology = liberal}}{\# \text{ideology = liberal}} \\ & = \frac{114}{175} = 0.65 \end{align*}` --- class: primary # Formal Definition **Conditional Probability**: The conditional probability of the outcome of interest `\(A\)` givent condition `\(B\)` is computed as: `$$P(A|B) = \frac{P(A \text{ and } B)}{P(B)}$$` --- class: primary # Multiplication rule We learned how to compute the joint probability of *independent* events, but this general multiplication rule can be used for any two events, `\(A\)` and `\(B\)`: `$$P(A \text{ and } B) = P(A | B) \times P(B)$$` - Note: When `\(A, B\)` are independent, `\(P(A|B) = P(A)\)`. - Note: This is just a re-arranging of the definition of conditional probability on the previous slide. --- class: primary # Conditional probability rules - For events `\(A_1, \dots, A_k\)` that are disjoint, and represent ALL outcomes for a random process, and for another event `\(B\)` (maybe from a different process): `$$P(A_1 | B) + \cdots + P(A_k|B) = 1$$` - For complement events, the rule also holds: `$$P(A^c | B) = 1 - P(A^c | B)$$` --- class: primary # Tree diagrams **Tree diagrams** are a tool to organize outcomes and probabilities around the structure of the data. Example for DREAM act data: <div class="figure" style="text-align: center"> <img src="img/dreamTree.png" alt="Tree diagram for DREAM act survey data" width="70%" /> <p class="caption">Tree diagram for DREAM act survey data</p> </div> --- class: primary # Bayes' Theorem - Idea: We know a conditional probability of the form `\(P(A|B)\)`. i.e. we know the probability of `\(A\)` conditioned on the event `\(B\)`. -- - BUT, we really are interested in the probability `\(P(B|A)\)`. -- - We sometimes say something like, "we want to flip (or reverse) the conditional" -- - Example: Suppose we have a piece of DNA evidence in a case that matches the defendant, call it `\(E\)`. We assume the forensic scientist knows `\(P(E|N)\)`, the probability that the evidence matching the defendant would be found *given* that the defendant is Not guilty. (This is the *random match probability* (RMP).) But, we are really interested in `\(P(N|E)\)`, the probability the defendant is Not guilty *given* the evidence `\(E\)`. -- - Note: Let `\(N^c = G\)` be the event that the defendant is Guilty. Then, `\(P(G|E) = 1- P(N|E)\)` since `\(G\)` and `\(N\)` are disjoint events. We are *really* interested in `\(P(G|E)\)`. --- class: primary # Bayes' Theorem Definition For 2 events, `\(A\)` and `\(B\)`: `$$P(A|B) = \frac{P(B|A)\times P(A)}{P(B)}$$` For disjoint events `\(A_1, \dots, A_k\)` that represent all possible outcomes of an process, and another event, `\(B\)`: `$$P(A_1 | B) = \frac{P(B|A_1)P(A_1)}{P(B|A_1)P(A_1) + P(B|A_2)P(A_2) + \cdots P(B|A_k)P(A_k)}$$` --- class: primary # Prosecutor's Fallacy In court cases, the **Prosecutor's Fallacy** occurs when someone treats the RMP as the probability that the defendant is innocent. This is NOT correct. As we saw: `\(P(E|N)\)` is what the forensic scientist knows. The prosecutor's fallacy occurs when someone incorrectly assumes `\(P(E|N) = P(N|E)\)`. It is called the Prosecutor's fallacy because it usually favors the prosecution over the defense. i.e. If `\(P(E|N) =1/1\)` million (like a piece of DNA evidence), the fallacy is stating that the probability the defendant is innocent is 1 in 1 million. --- class: primary # Your Turn 2.2.1 Suppose you have 2 events, `\(A, B\)`. All you know about these events is that `\(P(A) = 0.3\)` and `\(P(B) = 0.7\)`. 1. Can you compute `\(P(A \text{ and } B)\)` if you only know `\(P(A)\)` and `\(P(B)\)`? 2. Assuming that events `\(A\)` and `\(B\)` arise from independent random processes. a. what is `\(P(A \text{ and } B)\)`? b. what is `\(P(A \text{ or } B)\)`? c. what is `\(P(A|B)\)`? 3. If we are given that `\(P(A \text{ and } B) = 0.1\)`, are the random variables giving rise to events A and B independent? 4. If we are given that `\(P(A \text{ and } B) = 0.1\)`, what is `\(P(A|B)\)`? --- class: primary # YT 2.2.1 (soln.) Suppose you have 2 events, `\(A, B\)`. All you know about these events is that `\(P(A) = 0.3\)` and `\(P(B) = 0.7\)`. 1. Can you compute `\(P(A \text{ and } B)\)` if you only know `\(P(A)\)` and `\(P(B)\)`? .red[No. You need to either know that A and B are independent or you need to know either P(A|B) or P(B|A).] 2. Assuming that events `\(A\)` and `\(B\)` arise from independent random processes. a. what is `\(P(A \text{ and } B)\)`? .red[P(A) x P(B) = 0.3 x 0.7 = 0.21] b. what is `\(P(A \text{ or } B)\)`? .red[P(A) + P(B) = 0.3 + 0.7 = 1] c. what is `\(P(A|B)\)`? .red[P(A|B) = P(A) = 0.3] 3. If we are given that `\(P(A \text{ and } B) = 0.1\)`, are the random variables giving rise to events A and B independent? .red[No. P(A and B) = 0.1 does not equal P(A) x P(B) = 0.21 ] 4. If we are given that `\(P(A \text{ and } B) = 0.1\)`, what is `\(P(A|B)\)`? .red[P(A|B) = P(A and B)/P(B) = 0.1/0.7 = 0.143] --- class: primary # Your Turn 2.2.2 Swaziland has the highest HIV prevalence in the world: 25.9% of this country’s population is infected with HIV. The ELISA test is one of the first and most accurate tests for HIV. For those who carry HIV, the ELISA test is 99.7% accurate. For those who do not carry HIV, the test is 92.6% accurate. If an individual from Swaziland has tested positive, what is the probability that he carries HIV? --- class: primary # YT 2.2.2 (soln.) .small[ Swaziland has the highest HIV prevalence in the world: 25.9% of this country’s population is infected with HIV. The ELISA test is one of the first and most accurate tests for HIV. For those who carry HIV, the ELISA test is 99.7% accurate. For those who do not carry HIV, the test is 92.6% accurate. If an individual from Swaziland has tested positive, what is the probability that he carries HIV?] .red[ `\(P(\text{status}=+) = 0.259\)`, so `\(P(\text{status}=-) = 0.741\)`. `\(P(\text{test}=+|\text{status}=+) = 0.997\)`, `\(P(\text{test}=-|\text{status}=-) = 0.926\)` ] .red[ `\(P(\text{status}=+|\text{test}=+) = \frac{P(\text{test}=+|\text{status}=+)\cdot P(\text{status}=+)}{P(\text{test}=+)}\)` `\(P(\text{status}=+|\text{test}=+) = \frac{P(\text{test}=+|\text{status}=+)\cdot P(\text{status}=+)}{P(\text{test}=+|\text{status}=+)\cdot P(\text{status}=+) + P(\text{test}=+|\text{status}=-)\cdot P(\text{status}=-)}\)` `\(P(\text{status}=+|\text{test}=+) = \frac{0.997 \times 0.259}{0.997 \times 0.259 + (1-.926) \times 0.741}\)` `\(P(\text{status}=+|\text{test}=+) = 0.825\)` ] --- class: primary # Your Turn 2.2.3 Lupus is a medical phenomenon where antibodies that are supposed to attack foreign cells to prevent infections instead see plasma proteins as foreign bodies, leading to a high risk of blood clotting. It is believed that 2% of the population suffer from this disease. The test is 98% accurate if a person actually has the disease. The test is 74% accurate if a person does not have the disease. There is a line from the Fox television show House that is often used after a patient tests positive for lupus: "It’s never lupus." Do you think there is truth to this statement? Use appropriate probabilities to support your answer. --- class: primary # YT 2.2.3 (soln.) .small[ Lupus is a medical phenomenon where antibodies that are supposed to attack foreign cells to prevent infections instead see plasma proteins as foreign bodies, leading to a high risk of blood clotting. It is believed that 2% of the population suffer from this disease. The test is 98% accurate if a person actually has the disease. The test is 74% accurate if a person does not have the disease. There is a line from the Fox television show House that is often used after a patient tests positive for lupus: ``It’s never lupus." Do you think there is truth to this statement? Use appropriate probabilities to support your answer. ] .red[ `\(P(\text{status} = + | \text{test} = +) = \frac{0.02*0.98}{0.02*0.98+0.98\cdot 0.26 } = 0.071\)` ]  --- class: inverse # Section 2.3: Random variables --- class: primary # Random Variable We call a variable or process with a numerical outcome a **random variable** - We denote random variables with a capital letter, like `\(X\)`, `\(Y\)`, or `\(Z\)` - Examples: `\(X\)` = result of rolling a die once; `\(Y =\)` annual income of an adult in the US; `\(Z =\)` amount of lead in ppm in a pane of glass - Observed outcomes of random variables are denoted with the corresponding lower case letter, like `\(x\)`, `\(y\)`, or `\(z\)` - Examples: Roll a die 3 times. Observe a 3, a 2, and a 1: `\(x_1 = 3, x_2 = 2, x_3 = 1\)`; Some incomes of adults in the US: my mom = \$0 (stay-at-home mom), Bill Gates = \$2.6 billion, Lebron James = \$31 million: `\(y_1 = 0, y_2 = 2.6 \times 10^9, y_3 = 31 \times 10^6\)`; Observations from the glass data: `\(z_1 = 1.090, z_2=1.005, z_3=1.059\)` --- class: primary # Expected value - The expected value of a random variable is the average value of it - It's what you *expect* the value to be if you observe a new value - Denoted `\(E(X)\)`: "the expected value of (the random variable) `\(X\)`" - For a discrete variable `\(X\)` (with finite number of outcomes `\(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_k\)`), the expected value of `\(X\)` is: `$$E(X) = x_1 \times P(X = x_1) + x_2 \times P(X = x_2) + \cdots x_k \times P(X = x_k)$$` Example: `\(E(X)\)` where `\(X\)` is a roll of a die. Outcome | `\(x_1=1\)` | `\(x_2=2\)` | `\(x_3=3\)` | `\(x_4=4\)` | `\(x_5=5\)` | `\(x_6=6\)` | :-------|:-------:|:------:|:-------:|:-------:|:-------:|:-------:| Probability | `\(\frac{1}{6}\)` | `\(\frac{1}{6}\)` | `\(\frac{1}{6}\)` | `\(\frac{1}{6}\)` | `\(\frac{1}{6}\)` | `\(\frac{1}{6}\)` | `$$E(X) = 1 \times \frac{1}{6} + 2 \times \frac{1}{6} + 3 \times \frac{1}{6} + 4 \times \frac{1}{6} + 5 \times \frac{1}{6} + 6 \times \frac{1}{6} = 3.5$$` --- class: primary # Variance - The **variance** of a random variable, describes the variability of it. - Denoted by `\(Var(X)\)` or `\(\sigma^2\)` - i.e. if you observe several values, how different are they expected to be from each other - For a discrete variable `\(X\)` (with finite number of outcomes `\(x_1, x_2, \dots, x_k\)`), the variance of `\(X\)` is: .small[ `$$\sigma^2 = (x_1- E(X))^2 \cdot P(X = x_1) + (x_2- E(X))^2 \cdot P(X = x_2) + \cdots + (x_k - E(X))^2 \cdot P(X = x_k)$$` ] Example: for `\(X\)`= roll of a die. Outcome | `\(x_1=1\)` | `\(x_2=2\)` | `\(x_3=3\)` | `\(x_4=4\)` | `\(x_5=5\)` | `\(x_6=6\)` | :-------|:-------:|:------:|:-------:|:-------:|:-------:|:-------:| `\((x_i - E(X))\)` | -2.5 | -1.5 | -0.5 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 2.5 | `\((x_i - E(X))^2\)` | 6.25 | 2.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 2.25 | 6.25 | `\(\sigma^2 = 2.92\)` --- class: primary # Standard deviation - The standard deviation of a random variable is a measure of how much you can expect an observation to differ from the mean by - Denoted `\(\sigma = \sqrt{\sigma^2}\)` - Is equal to the square root of the variance --- class: primary # Your Turn 2.3.1 A portfolio's value increases by 18% during a financial boom and by 9% during normal times. It decreases by 12% during a recession. What is the expected return on this portfolio if each scenario is equally likely? --- class: primary # YT 2.3.1 (soln.) A portfolio's value increases by 18% during a financial boom and by 9% during normal times. It decreases by 12% during a recession. What is the expected return on this portfolio if each scenario is equally likely? .red[ Let `\(R\)` denote the return of the portfolio. `\(R\)` has 3 outomes: 0.18, 0.09, and -0.12. Each outcome has probability `\(\frac{1}{3}\)`. `\(E[R] = \frac{1}{3}(0.18 + 0.09 + (-0.12)) = \frac{0.15}{3} = 0.05\)` ] --- class: primary # Your Turn 2.3.2 The game of American roulette involves spinning a wheel with 38 slots: 18 red, 18 black, and 2 green. A ball is spun onto the wheel and will eventually land in a slot, where each slot has an equal chance of capturing the ball. Gamblers can place bets on red or black. If the ball lands on their color, they double their money. If it lands on another color, they lose their money. Suppose you bet $1 on red. What’s the expected value and standard deviation of your winnings? --- class: primary # YT 2.3.2 (soln.) .small[ The game of American roulette involves spinning a wheel with 38 slots: 18 red, 18 black, and 2 green. A ball is spun onto the wheel and will eventually land in a slot, where each slot has an equal chance of capturing the ball. Gamblers can place bets on red or black. If the ball lands on their color, they double their money. If it lands on another color, they lose their money. Suppose you bet $1 on red. What’s the expected value and standard deviation of your winnings? ] .red[ Outcome: | Red | Black | Green :--- | :-: | :--: | :---: `\(x\)` | $1 | -$1 | -$1 `\(P(X= x)\)` | `\(\frac{18}{38} = 0.474\)` | `\(\frac{18}{38} = 0.474\)` | `\(\frac{2}{38} = 0.053\)` `\(E(X)\)` | $ -0.053 `\((x - E(X))\)` | 1.053 | -0.947 | -0.947 `\((x - E(X))^2\)` | 1.108 | 0.897 | 0.897 `\(P(X = x)\cdot(x - E(X))^2\)` | 0.525 | 0.425 | 0.047 `\(Var(X)\)` | 0.997 `\(sd(X)\)` | `\(\sqrt{0.997} = 0.999\)` ] --- class: inverse # Section 2.4: Continuous distributions --- class: primary # Recall: Histogram Let's look at the lead content of our glass samples: <img src="probability_files/figure-html/glasslead-1.png" width="80%" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> What makes continuous variables different from discrete variables? --- class: primary # Density - A **probability density function** is a smooth curve that represents the relative frequency of outcomes of a continuous random variable. - The area under the curve is 1. (Represents summing up all probabilities of disjoint outcomes) <img src="probability_files/figure-html/glassleaddens-1.png" width=".5\linewidth" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: primary # Probabilities from densities - Since the probability of any one outcome is 0, we need to look at ranges of outcomes - Example: `\(P(0.99 \leq \text{lead concentration (ppm)} \leq 1.01) = 0.0379\)` but `\(P(\text{lead concentration (ppm)}=1.00) = 0\)` <img src="probability_files/figure-html/glassleadprob-1.png" width=".5\linewidth" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: primary # Your Turn 2.4.1 .small[ The histogram shown below represents the concentration (in ppm) of lithium (Li) in 144 measurements in 12 different panes of glass. 1. What fraction of the glass fragments have Li concentration less than 2.5 ppm? 2. What fraction of the glass fragments have Li concentration between 2.5 and 2.75 ppm? 3. What fraction of the glass fragments have Li concentration between 2.75 and 3.5 ppm? ] <img src="probability_files/figure-html/cathist-1.png" width=".6\linewidth" style="display: block; margin: auto;" /> --- class: primary # YT 2.4.1 (soln.) .small[ The histogram shown below represents the concentration (in ppm) of lithium (Li) in 144 measurements in 12 different panes of glass. 1. What fraction of the glass fragments have Li concentration less than 2.5 ppm? .red[(29+32)/144 = 0.424] 2. What fraction of the glass fragments have Li concentration between 2.5 and 2.75 ppm? .red[21/144 = 0.146] 3. What fraction of the glass fragments have Li concentration between 2.75 and 3.5 ppm? .red[26/144 = 0.181] ] <img src="probability_files/figure-html/cathist2-1.png" width=".6\linewidth" style="display: block; margin: auto;" />